If you are researching cobot palletising cycle time, chances are you are trying to answer one simple question that vendors rarely answer clearly:

“How many cases per minute will this actually run on my production line?”

On paper, a robotic palletiser looks fast. In reality, palletising speed is limited by far more than the robot’s headline speed. What matters is how the entire production line, from upstream conveyors to the final pallet position, behaves once real boxes, real stacking patterns, and real safety constraints are applied.

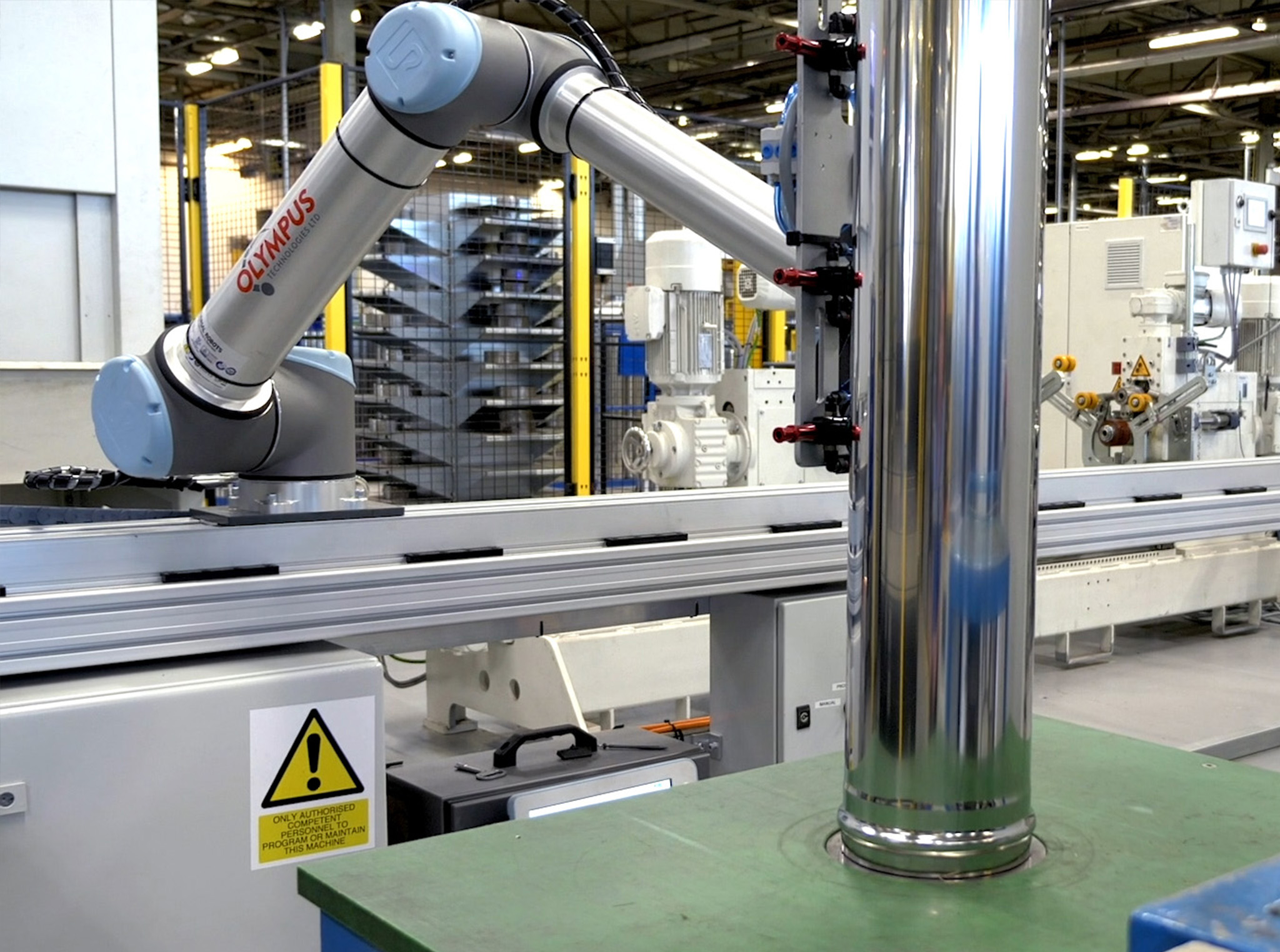

At Olympus Technologies, we design and implement flexible automation systems every week. This guide explains how to calculate realistic cases per minute, why brochure numbers rarely hold up, and the seven real bottlenecks that cap palletising throughput in live operations.

If your CPM estimate ignores settle time, pattern logic, or payload limits, it is wrong.

Why Palletising Speed Is Almost Always Overstated

Robot speed is not the same as line throughput.

A palletising cobot may be capable of impressive motion speeds, but cycle time is calculated based on the slowest constraint in the system, not the fastest component. In practice, the palletiser sits at the final stage of the process. Any delay or failure here stops products leaving the facility, even if upstream production is running perfectly.

Common reasons real palletising performance falls short of expectations include:

- Conservative safety settings in collaborative workspaces

- Payload capacity limits at maximum reach

- Conveyor gaps and inconsistent product flow

- Complex stacking patterns and product changeovers

- Settle time to avoid product damage or label scuffing

This guide gives you a practical model for estimating throughput, and the constraint thinking needed to review palletising proposals properly.

The Simple Cobot Palletising Cycle-Time Model

Every palletising cycle, regardless of robot brand, follows the same basic method:

Pick → Travel → Place → Settle

Total cycle time is the sum of these four steps. Cases per minute is then calculated from that cycle time.

Pick

Pick time depends heavily on upstream processes.

Conveyor gap consistency is critical. If products arrive too close together, the robot must wait. If they arrive too far apart, the palletiser starves. This is often the first hidden bottleneck on production lines.

Single-pick systems are simpler but slower. Multi-pick systems increase throughput, but only if the end-of-arm tooling, payload capacity, product consistency and pallet pattern allow it.

Travel

Travel time is influenced more by distance and acceleration limits than by top speed.

Vertical travel increases cycle time quickly, especially when approach heights are set conservatively to protect packaging or maintain load integrity. Horizontal reach matters too. As the robotic arm approaches its maximum reach, speed is automatically derated to maintain control and safety.

Place

Placement time is affected by stacking pattern accuracy and orientation constraints.

If labels must face out for quality control, traceability, or compliance, rotations and offsets are unavoidable. These movements add time, even though they look minor in simulation.

Settle

Settle time is the most underestimated factor in palletising.

It is the pause after placement that allows boxes to stabilise before the robot releases. Without it, product damage, shifting loads, and pallet failure increase sharply.

Ironically, slowing down here often increases overall throughput by preventing downstream failures.

Cycle-Time Elements and Typical Ranges

| Step | Typical time (s) | What increases it | What reduces it |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pick | 0.6–1.2 | Poor conveyor gaps, heavy loads | Consistent infeed, multi-pick |

| Travel | 0.8–1.8 | Long reach, vertical clearance | Compact layout |

| Place | 0.5–1.0 | Orientation rules, tight stacking | Simple patterns |

| Settle | 0.3–0.8 | Deformable packaging | Stable cartons |

The 7 Real Bottlenecks That Cap Palletising Speed

Bottleneck 1: End-Effector Limits

Vacuum grippers often require blowoff time after placing. Clamp systems introduce open and close delays. Hybrid tools add capability but also complexity.

The end-of-arm tooling often sets the pace, not the robot.

Bottleneck 2: Approach Height and Clearance

Conservative Z-moves are used to reduce collision risk and packaging damage. These add significant time, especially with tall pallet builds or flexible materials.

Bottleneck 3: Layer Changes and Pattern Logic

Indexing between layers, offsets, and rotations introduce logic delays. Poorly designed stacking patterns increase travel distance, restrict multi-picking and reduce palletiser efficiency.

Bottleneck 4: Interlayers and Slip Sheets

Interlayers add extra motions. Whether sheets are fed manually or automatically makes a measurable difference to throughput.

Bottleneck 5: Conveyor Gaps and Infeed Control

Accumulation does not equal control. Without guaranteed gaps, the palletiser spends time waiting rather than stacking.

Bottleneck 6: Settle Time and Label Scuff Avoidance

Reducing settle time increases product damage and pallet instability. Slowing the robot slightly often improves overall line reliability.

Bottleneck 7: Payload Derating at Reach

As payload increases and reach extends, cobots automatically reduce speed to maintain stability and safety. This is built into the control system and cannot be bypassed.

Mixed SKUs: Why Changeovers Kill CPM

Single-SKU palletising is the fastest scenario. High-mix production is where reality bites.

Pattern Complexity

Irregular pallet patterns restrict multi picking capability and require more complex end-of-arm-tooling, with variations in box heights, and weights all contributing to slowdown and travel time.

Product Changeovers

Recipe switching, operator confirmation, full-pallet changeovers and system checks introduce non-productive time that rarely appears in speed claims.

| Scenario | Typical CPM | Primary limiter | Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single SKU | 8–14 | Payload and reach | Optimised pattern |

| Mixed SKU | 4–8 | Logic and changeovers | Standardised recipes |

A Practical Cases-Per-Minute Calculator

The baseline calculation is simple:

Cases per minute = 60 ÷ cycle time (seconds)

If one cycle takes 4.5 seconds, CPM is 13.3.

To convert to cases per hour:

CPH = CPM × 60

Always calculate using conservative assumptions. Real performance improves when bottlenecks are removed, not when numbers are inflated on day one. A palletisers capability to clear a backlog of product must also be considered. A palletising system should be capable of palletising cases faster than it recieves them.

When a 7th Axis or Track Changes the Maths

Rails increase reach and allow multiple pallet positions, but they also add control complexity.

A 7th axis helps when reach, not speed, is the limiting factor. It does not magically increase cycle speed and can reduce reliability if poorly integrated.

UR Palletising Speed vs Reality

UR palletising figures often quote ideal conditions: short reach, light payloads, simple patterns.

In real applications, payload capacity, duty cycle, safety limits, and packaging variability reduce achievable speed. UR cobots excel in flexibility and ease of coding/programming, but like all collaborative robots, they prioritise safety and control over raw pace.

How to Specify Throughput in an RFQ Without Getting Burned

Before requesting quotes, define:

- Required average vs peak CPM

- SKU mix assumptions

- Stacking patterns for all SKUs

- Interlayers and frequency

- Allowed settle time

- Acceptable damage rate

- Changeover expectations

This positions you as a technically informed buyer and avoids disappointment later.

Why Olympus Technologies Approaches Throughput Differently

At Olympus Technologies, we design palletising systems as part of a complete solution, not isolated robotic cells. We consider:

- Upstream conveyors and packaging

- Downstream storage and dispatch

- SKU data and stacking patterns

- Safety, compliance, and operator training

- Long-term reliability and maintenance

That same systems thinking carries across our work in palletising automation, case packing, machine tending, press brake tending, welding, laser welding, and dispensing systems.

If throughput matters, the conversation has to start with constraints, not claims.

Final Thought

Cobot palletising speed is not a single number. It is the outcome of payload, reach, layout, software, safety, packaging, and human interaction working together.

When those factors are engineered properly, cobot palletising delivers reliable throughput, improved safety, and fast payback. When they are ignored, even the fastest robot becomes the slowest part of the line.

If you want help calculating realistic CPM for your facility, or reviewing a palletising proposal before you commit, Olympus Technologies is ready to support the project properly from concept to installation.

FAQs: Cobot Palletising Speed, Safety and Real-World Performance

1. Why does palletising speed drop with heavier products or larger boxes?

Heavier products require slower, more controlled movements in cobot palletising systems to maintain stability, accuracy, and load integrity. As payload increases, cobots automatically reduce speed, especially at maximum reach, to stay within torque limits and safety thresholds. Larger boxes and irregular shapes also increase settle time and placement accuracy requirements, which further reduces achievable cases per minute. This is why palletising speed must always be calculated based on real product weight, size, and stacking pattern rather than brochure figures.

2. Do safety standards limit cobot palletising cycle time?

Yes. Cobot palletisers must comply with international safety standards such as ISO 10218 and ISO/TS 15066, which govern collaborative operation alongside human workers. These standards require power and force limiting, collision detection, and controlled speeds in shared workspaces. While this can cap maximum speed compared to fenced industrial robots, it allows cobots to operate safely without extensive safety guarding, making them suitable for open layouts following a proper risk assessment and safety configuration.

3. How do cobot palletisers improve safety and efficiency compared to manual palletising?

Cobot palletisers automate repetitive lifting and stacking tasks, significantly reducing repetitive strain injuries associated with manual palletising. By handling the physical workload, cobots allow operators to focus on higher-value tasks such as quality control, inspection, maintenance, and line supervision. This improves workplace safety, reduces labour fatigue, and increases operational efficiency across end-of-line processes.

4. Can cobot palletisers handle different box sizes, shapes, and industries?

With the right end-of-arm tooling and software, cobot palletisers can handle a wide range of box sizes, shapes, and weights. Options include vacuum grippers, mechanical clamps, and multi-zone grippers, combined with vision systems or sensors for precise placement. This adaptability makes cobot palletising suitable for industries including warehousing, food production, consumer goods, pharmaceuticals, general manufacturing, and e-commerce operations where product formats frequently change.

5. What are the most common causes of bottlenecks in cobot palletising systems?

The most common sign of a bottleneck is product accumulation at a specific stage of the production line, often at the end-of-line palletising area. Typical causes include inefficient pallet patterns, excessive robot travel distances, poor conveyor gap control, restrictive cell layouts, and insufficient maintenance of critical components such as end-of-arm tooling and sensors. Because palletising is the final production stage before goods leave the facility, any delay here stops dispatch entirely, even if upstream processes are running perfectly. Regular preventative maintenance, efficient layout design, and optimised pallet logic are essential to maintain throughput and reliability.